In 2016, the then commander-in-chief of the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army), Timoleón Jiménez (today Rodrigo Lodoño), used a pen made with ammunition to sign the Peace Agreement. The document, which was also signed by the then president, Juan Manuel Santos, finally sealed peace in a country that was facing 53 years of war, of armed conflict between the guerrillas and the State. This gesture opened a new chapter in Colombia’s history, where the solution to the problem would no longer be a military response.

The guerrillas trusted in this agreement, they were protagonists in the construction of this dialogue and gave up all their weapons. Absolutely everything. The delivery was supervised by the UN. Containers full of pistols, revolvers, rifles, and grenades were locked with huge padlocks, in a public broadcast, followed live by political authorities from different countries, as well as the international mechanisms that supervised all the action. That day marked the end of the war. From that moment on, none of the members of the guerrilla could resort to arms. And then, what happens the morning after? A new life. But for that, you need guarantees.

The agreement was built during four years, through the so-called “peace dialogues”, a process carried out in Havana, after Cuba kindly ceded its territory, so that the conversation would take place in a neutral region; neither party had an advantage or advantage vulnerability. In addition to the UN, dozens of ministers and presidents from other countries followed these dialogues to ensure security and legitimacy. Hundreds of former guerrilleros participated in the negotiation tables because someone who had to use arms to defend himself has a lot to say and everyone needs to be heard.

From this meticulous dialogue, an agreement was built. It includes many points, like, social reintegration, the guarantee of security, the right to land, to work, reparation and justice for the victims, among others. It is a complex agreement, and its implementation requires a strong political will and commitment with the hard task of building peace. A country that has lived 50 years of war is torn. It is not just the survivors, thousands of them mutilated by the conflict, who need care; it is a whole network of people and communities that were affected by the war and now they need to relearn how to live and how to be able to do so. The numbers are frightening: 53 years of war left 250,000 dead and more than 9 million forcibly displaced, the largest internal displacement in the history of the Americas.

The problem was that shortly after the Accord, Colombia elected a far-right president, Ivan Duque, sponsored by FARC archenemy and drug trafficking friend, Álvaro Uribe. From the beginning, he said he would make no effort to implement the agreement. Even worse, he said he would “break” the agreement (“tear to shreds,” to be specific). This attitude was a bucket of cold water for all those who participated in the peace process, but for the ex-guerrillas, and the Colombian people of the affected territories, it was a real attempt at life.

Since then, several regions of the country have been vulnerable to paramilitary groups and drug trafficking. It cannot be said that a new war has begun because now one side has no defense. What has been going on are real massacres. Between 2016 and 2020, 421 human rights defenders and activists were killed. In 2022 alone, 38 massacres have already been perpetrated in different regions of the country. On average, a social activist is killed every other day. These people are unionized workers, teachers, students, peasants, housewives, and general service workers. Diario el Indepaz (Institute of Studies for the Development of Peace) publishes the reports of the massacres and presents the profile of the victims. These are normal people, who are being killed in cold blood with no possibility of defense.

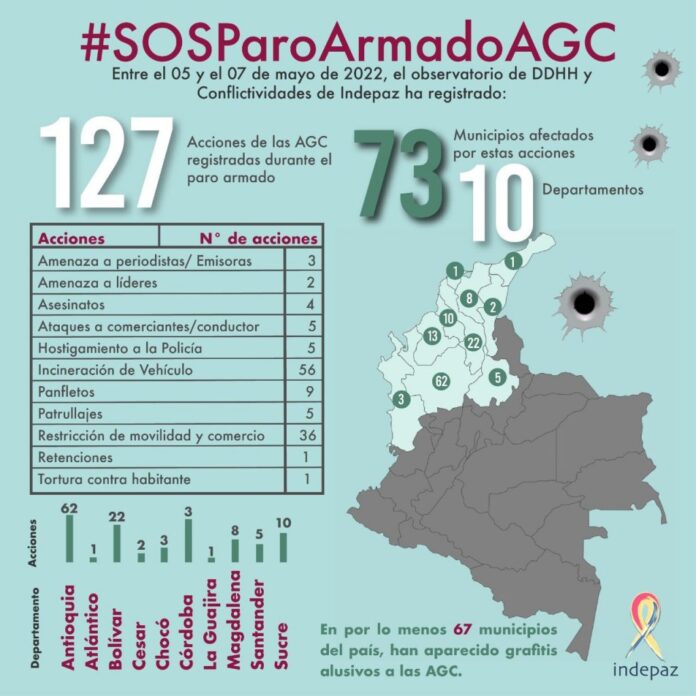

The escalation of violence sometimes intensifies. This is what is happening right now as you read this text. In the first days of May, a paramilitary group calling itself “Clan del Golfo”, promoted what was called an “armed camp”, a kind of “strike”, armed. 73 municipalities in the northern region of the country and more than ten departments (the equivalent of states in Brazil) were affected. During the 3 days of the “strike”, 4 people were killed, at least one tortured, journalists were threatened and entire cities were subjected to curfews.

The Commission accompanying the implementation of the Peace Agreement, CSM-Commons, requires the State to comply with point 3.4. of the Agreement, which determines “the importance and necessity of dismantling the successor groups of paramilitarism”. This point promotes mechanisms of persecution, judicialization, and dismantling of these organizations, for which a Special Investigation Unit was created. But the actions of this detachment have been scarce, almost nil. The biggest evidence is that the country is with the entire Northern region under threat from an armed group right now.

Meanwhile, presidential elections are being held. And the FARC, in addition to defending its former guerrillas and territories, also assumes the challenge of building peace through political means, by holding public office. This is the story of the Commons, the political party that was born after the laying down of arms.

The Commons – the word as a weapon

After leaving the army, the old guerrilla initially chose to change only the meaning of the acronym, and stay with the name FARC, whose letters now mean “Alternative Revolutionary Force of the Common.” After effectively entering political life as a party, and beginning to build the peace process together with civil society, they decided to simplify and “Commons” was born.

The challenges of those who spent their lives with a backpack on their backs and a rifle on their shoulders in the Colombian jungle, to reintegrate into society and begin to participate in public life are innumerable. Therefore, one of the points of the Agreement guarantees that the Communist Party is entitled to a certain number of seats in both the Senate and the House of Representatives for three terms, even without having obtained enough votes to occupy them. Thus, the Commons currently has 3 senators and 4 representatives.

When it comes to composing a blackboard, they continue to walk alone. But in these elections, they are linked to the Historical Pact, the left-wing coalition that leads the polls with candidate Gustavo Petro and Vice President Francia Márquez. The candidacies of the Commons, not having the – let’s say – “concern” of choosing a candidate, are pedagogical and serve to broaden the discourse of peacebuilding, and bring the former guerrillas closer to society. Agendas such as the recovery of war-affected territories for agriculture, the generation of employment, the guarantee of security and the right to culture and citizenship, and gender and race policies are the most discussed issues.

Peace tastes like honey, beer, and coffee

But what about ordinary people, what do they do? Those who became part of civilian life but did not enter politics, what do they do after the war? According to the Agency for Reinstatement, a government entity, about 13,000 people are currently in the process of being reinstated. After laying down their arms, these people need to be able to build a “normal” life. Having a job, housing, the right to health, education, transportation, security… like any citizen.

In Colombia, in addition to the war, there is the issue of drugs. Thousands of peasants are engaged in coca leaf production – and many of them do this because they live in regions dominated by drug trafficking without conditions to develop another crop. To devote themselves to something else, they need to have security and support to produce. This is also one of the points of the Agreement. According to government data, there are 3,575 approved projects, which benefit some 7,600 ex-combatants, so that they can dedicate themselves to a new professional task, without weapons, links to trafficking, or any type of violence.

These projects have given rise to entire cooperatives producing coffee, honey, organic food, dairy and sausages, clothing, accessories, and craft beer, which is Colombia’s best-known peace product. On the internet, it is possible to find the profiles of these new solidarity economy companies on Twitter and Instagram. The stores are very similar to those of any metropolis: a cool design, fashion products, the healthy ones of the time. A contemporary proposal, and a kind and supportive response to those who believe that the way out of war is militarization.

It is well known that Colombia produces one of the best and most coveted coffees in the world. This is why, Café Maru is a coffee with a taste of peace, born in the hands of ex-combatants. The honey that comes from the mountain also gives flavor to this process, watered with hope and beer. La Trocha is a craft beer produced by a factory run by former guerrillas in the Tolima region. Clothing and accessories are also on the production list of those who are now dedicated to building peace and working with their hands to ensure daily sustenance.

To continue on this path to peace, Colombia needs a Senate, a House and a president different from that of Iván Duque, and a politician committed to the Peace Agreement. Let us hope that the candidate currently leading the polls will succeed and that Latin America can finally be a continent free of wars.

Translation: Sabrina Márquez for ALAI