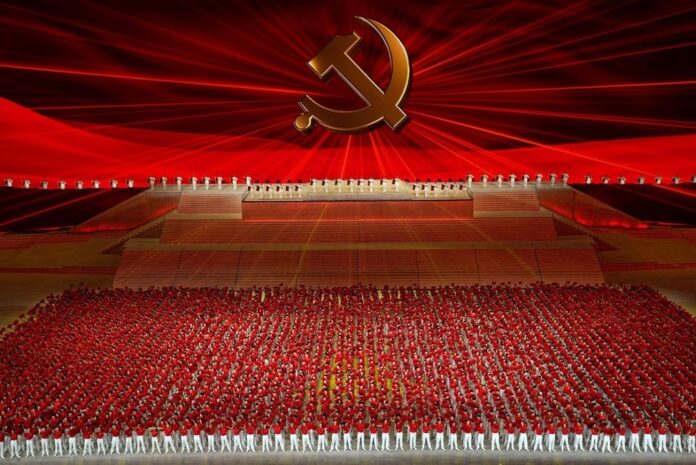

In the year 2021, the Communist Party of China[1] reached its first century as a political organisation. During that century, it had steered the destinies of the Asian giant for 72 years, during which it has experienced the most grueling factional conflicts, the greatest processes of social experimentation ever seen in the world and the most rapid process of modernisation and industrialisation in recent history.

It has also been the subject of the fiercest criticism from the Western left and right, accused of both promoting liberal deviations and marching contrary to the Western Marxist tradition.

China represents the most virtuous, innovative and brilliant bastion of authentic communist thought, becoming a mecca for many of the political leaders of the various progressive waves of recent times. For these reasons we could say that the CPC has been and remains one of the most influential communist parties of the 20th century and so far in the 21st century.

The history of the CPC “has been the history of the permanent experience of its cadres and a permanent theoretical experimentation with a constant search for the truth in facts”, as Xi Jinping[2], the current General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and Chairman of the Central Military Commission, put it.

Seeking the truth in facts has been the main tool in the party’s political practice for the past 72 years, renewing and consolidating new horizons and ways of implementing Marxist-Leninist theory.

For some, the party’s turn towards reform and openness, over the last 43 years[3], has meant a betrayal and a deviation from the main values of Marxism. Similarly, for most analysts, China’s recent history is the history of the recapitalisation of its economy; and the last 50 years of the party, the history of its surrender and abandonment of the socialist project.

Most of these views are held with partial or total ignorance of the historical processes that have led the CPC to develop new ways and methods of strengthening and consolidating China. Without an understanding of these dynamics particular to Chinese Marxist thought, or even a consideration of its goals and objectives, it is simply impossible to understand the ideology developed by the party.

As historian Eric Hobsbawm made clear, the everyday practice or “everyday” political theory of Marxism was not fully developed by Marx. Elements such as party tactics, the type of party, economic policies and party-mass relations were never fully developed and were not even part of the immediate ambitions of Marx or Engels[4].

On these issues there are only loose and scattered elements, in many cases conjunctural and in others partial. However, it is possible, the same author argues, to outline the elements that could serve to consolidate the aspirations of Marxism around political intentions.

”All of Marx’s political controversies in his later years were in defence of the threefold concept of (a) a proletarian class political movement; (b) a revolution seen not simply as a transfer of power… but as a crucial moment initiating a complex period of transmission, not easily predictable; and (c) the consequently necessary maintenance of a system of political authority, a revolutionary and transitional form of the state”[5].

Around these three points we could analyse the theoretical and tactical history of the CPC, the different contributions of its leaders and the different theories and thinking that today give the CPC its very particular character, which would also allow us to examine in a more binding and comprehensive way the complex historical process around which it was forged.

Xi Jinping and the 100 years of the CPC

On 1 July 2021, Xi Jinping addressed the world in an emotional speech celebrating 100 years of the CPC. Here we will quote excerpts from this speech and then comment on and evaluate the contributions and elements that the various leaders added to the line of thought and theory of the party under the principles outlined above.

“On behalf of the Party and the people, I solemnly declare here that, through the uninterrupted struggle of the whole Party and the people of all ethnic groups of the country, we have fulfilled the goal of struggle set for the first centenary, completing the comprehensive construction of a modestly well-off society in the vast Chinese territory, with the question of absolute poverty historically solved, and that we are advancing with boundless vigour towards the goal of struggle set for the second centenary: completing the comprehensive construction of a powerful modern socialist country. This is a great glory of the Chinese nation, the Chinese people and the CPC!

“After the Opium War of 1840, with China step by step turned into a semi-colonial and semi-feudal society, with the country humiliated, the people devastated and its civilisation covered in dust, the Chinese nation suffered an unprecedented misfortune. The realisation of its great revitalisation therefore became its and the people’s greatest dream.

“Successively, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement, the Reform Movement of 1898, the Yihetuan Movement and the Revolution of 1911, emerged, as well as all kinds of national salvation projects, but they all ended in failure. China urgently needed a new ideology to guide the national salvation movement and a new organisation to unite the revolutionary forces. The cannon fire of the October Revolution brought Marxism-Leninism to China. In response to the needs of the times, the CPC was born in the process of both the great awakening of the Chinese people and nation and the close integration of Marxism-Leninism with the Chinese labour movement. The birth of the communist party in China, a momentous and epoch-making event, profoundly changed the course and process of the development of the Chinese nation since modern times, the future and destiny of the Chinese nation and people, and the trend and shape of world development”[6].

The CPC initially took the Soviet Marxist-Leninist line as its main foundation, but later distanced itself from it[7]. After a bitter 28-year struggle since its founding in 1921, the CPC came to power and its great leader Mao Zedong declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China on 1 October 1949.

During its first 50 years, the party went through a great process of persecution and ideological struggle, sometimes less radical, as during the so-called “Hundred Flowers Campaign”, and sometimes more violent, as during the “Anti-Rightist Campaign” of 1957-1959, the latter specifically targeting the most educated sectors of the party and society under the accusation of ideological sedition.

These last two campaigns, according to Mao, were linked to the imperative need, in the face of imperialist dangers “to form a party that could use dialectical tools and not dissidence to be able to resolve its conflicts and maintain unity”.[8]

Subsequently, faced with the economic problem, Mao proposed the “Great Leap Forward” between 1958 and 1962, which was the greatest social experiment of which there is any reference; the intention was to achieve accelerated Chinese industrialisation, and this experience would become the first adages of what would later become the four modernisations.

The exhausting failure of the Great Leap Forward was a major setback for Mao, who was removed by the party from his post as President of the Republic and replaced by Liu Shaoqi, although Mao remained as party leader, the questioning generated in these years reopened new fissures within the party.

It was in this context that the so-called “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” was unleashed from 1966 to 1976, aimed at combating the reformist elements in the party and consolidating the party’s ideological and propaganda control. During this period prominent figures were tried and imprisoned by the so-called “Red Guard”[9], Liu Shaoqi himself was arrested and dismissed during this process, also Mao’s later successor, Deng Xiaoping suffered a similar fate. In the midst of that confusion emerged the so-called gang of four; Jiang Qing Mao’s wife, Zhang Chunqiao journalist, writer and Red Guard leader, Yao Wenyuan and Wang Hongwen, the latter, the visible head of the Red Guard and officer in charge of security for senior party officials.

The gang of four would mark a dark period in the history of the party and of China itself; the party itself officially recognises this stage of its history as its darkest moment[10].

After Mao’s death in 1976, Hua Guofeng was elected as Mao’s successor by the party, this meant the beginning of an orderly process, called “Boluan Fanzheng“, during this period important party leaders were rehabilitated, among them Deng Xiaoping and the Gang of Four were imprisoned for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution.

For Chinese history, the Boluan Fanzheng is recognised as a moment of calm after so many years of turbulence inside and outside the party.

In those years the so-called premise of “the two whatevers” was formulated as a programmatic rule in the party, which meant the defence “with firmness [of] all those political decisions taken by Chairman Mao, and the respect from beginning to end and without wavering of all those instructions given by Chairman Mao”[11].

Under this slogan, some factions of the party wanted to continue to hold on to their share of power against the so-called new ideas, or against the reformists. Deng Xiaoping strongly criticised this position and called for seeking the truth in the facts[12] and “giving the possibility, in new times, to formulate new ideas”[13] following Mao’s teachings.

This meant a breakthrough in the party and the consolidation within it of Deng’s position over that of Hua Guofeng and of the more radical reformist wing against the conservative wing in the battle of ideas.

Deng Xiaoping: reform and openness

An important element in the party’s historical construction has been the designation and definition of the party’s great goal, namely the great revitalisation of China and the consolidation of a modestly affluent society[14], all framed within the liberation of the productive forces and the construction of mechanisms within the state structure to promote them[15], and under the unerring tactic of the four modernisations, namely:

– Modernisation of agriculture, allowing for family ownership and decisions around production units, the form of production and the dynamics of excedental sales.

– Industrial modernisation, allowing foreign investment, creating space for experimentation with private capital (special economic zones), promoting incentives for workers, as well as free choice of work. State price-fixing was partially ended and greater freedom granted to set wages, hire and fire workers, and private enterprises were encouraged to flourish.

–Modernisation of the army, by dismissing the Red Guard and increasing the size of the regular army, as well as the consolidation of ranks and hierarchies within the military.

–Modernising science and technology, by investing heavily in schools and universities, strengthening admission policies and promoting scholarships to study abroad, thus boosting research and technological development.

Speaking of Deng Xiaoping’s great contributions, Xi Jinping in 2018 on the occasion of the commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the Reform and Openness stated:

“In overcoming leftist errors [Deng Xiaoping] reaffirmed the need to comprehensively and correctly understand Mao Zedong’s thought as a whole, as a scientific system. He valued the debates on the criteria for testing the truth and succeeded in putting an end to the class struggle as a line of work. And by re-establishing Marxism as the guiding principle of our ideological, political and organisational work, he set China and the Party on the path of modernisation[16].

As early as 1979, Deng argued that under the practices and methods of reform and openness, China would achieve a modestly affluent society by the beginning of the 21st century[17]. This demonstrates the great foresight and planning framework that the party was able to generate on the issue of China’s development, making reform and openness the party’s doctrinal line.

A decade after this foresight, Xiaoping was eclipsed by the events of Tiananmen Square, and had to delegate his position to Jiang Zemin, who was to usher in the third generation of revolutionary leaders.

By that time, China had already strengthened its regional position as an emerging economy, and although it was still burdened with high levels of poverty, there was already a representative entrepreneurial class in the country, supported by a robust industrial sector.

It is worth considering that despite the economic reforms and major theoretical concessions that the state had promoted, political openness and debate still lagged far behind, with the emerging classes demanding some form of representation vis-à-vis the state.

Deng had already shifted the fundamental problem of the party (class struggle) towards the national task of modernisation, but the problem of class dynamics had remained somewhat up in the air. In this line, thanks to historical necessity and also focusing on the maxim “new times, new ideas”, Jiang Zemin formulated the political theory of “triple representativeness”.

This theory would come to renew the role of the CPC in the new times of modernisation and openness; henceforth the party would not only be the agitator and representative arm of the proletariat, but now its social base would be broadened to include the new social strata:

“As reform and openness deepen and the economy and culture develop, the ranks of the working class in our country are steadily being strengthened and their quality raised. The working class, including the intelligentsia, and the broad peasantry are always the essential force behind the development of the advanced productive forces of our country and the all-round progress of our society. The social strata that have emerged in the midst of social change, such as the founders and technicians of the non-officially owned scientific-technological enterprises, the administrative and technical staff employed by the enterprises of foreign capital, the self-employed owners, private entrepreneurs, people employed in intermediary organisations and independent professionals, are all builders of the cause of socialism with Chinese peculiarities. As for the people of the various social strata who contribute their strength to the prosperity and strength of the country, we should unite with them, encourage their enterprising spirit, protect their legitimate rights and interests, and commend the outstanding elements among them, thus striving to bring about a situation in which all members of the people can make contributions according to their ability, each have his or her proper place and all live together in harmony.”[18]

Thanks to this new theory or thinking, entrepreneurs and big businessmen, also called advanced productive forces, were to find resources and protection from the party and not only that, but they could also have representation and power in the party[19], this has undoubtedly been one of the most controversial points of socialism with Chinese peculiarities.

The 21st century also brought for China the need to generate different policies in its development model, issues such as inequality were evident elements, it was not enough to lift people out of poverty, it was also necessary to continue improving the quality of life in the same way as political participation, the old limits referring to China’s backwardness in terms of technology were also beginning to disappear, which merited a reformulation in the social aspirations of the party. Here the contribution would come not from Zemin but from his successor Hu Jintao.

Jintao was to put forward the concept of the “Scientific Model of Development”, with the premise of achieving the “harmonious society” aimed at progressively decreasing social tensions in China and further expanding the margins of benefit of reform and openness in the broadest sectors of society.

This policy of a scientific model of development has enabled China to make great strides in the last decade in terms of targeting resources to fight poverty and improving social guarantees.

In the last four decades, more than 740 million Chinese have been lifted out of poverty under these policies.

Basic pension insurance covers more than 900 million Chinese, health insurance covers more than 1.3 billion Chinese, the urbanisation rate has reached 58.5%, an increase of 40.6% compared to 1978, the life expectancy of the Chinese has increased from an average of 67.8 years in 1981 to 76.7 years in 2017[20]. These are all achievements of reform and openness, carried out by the party.

Xi Jinping and the new era of Chinese socialism

According to Xi Jinping – in line with the official history of the Chinese Communist Party – the great experiment of “socialism with Chinese peculiarities” can be divided into three generations. The first would begin with Mao Zedong who “provided valuable experience, laid the theoretical and material preparations for the beginning of the new period of socialism with Chinese peculiarities”[21]. A second generation, starting with the reform and openness in the late 1970s, centred on Deng Xiaoping who initiated Socialism with Chinese peculiarities. And finally, a third generation of party politicians who see openness and globalisation as the cornerstone of development, under the slogan “Go Global”. This third generation was to come in headed by Jiang Zemin, who “successfully propelled socialism with Chinese peculiarities into the 21st century”[22] and in the case of Hu Jintao, who laid the foundations for formalising the discussion of what the China of the 21st century would be like.

Within the framework of the new era for socialism with Chinese peculiarities and with Xi Jinping at its head, great challenges are looming, among them the need to strengthen the ideological condition of the party and the need to deepen Marxism in the face of the new times.

Now that the goal of a modestly affluent society has been achieved, the next challenge for the second centenary (2049 centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China) is to make China a technological and economic power in the world, under the innovative strategy of the “Four Integrations”.

“In the new expedition, we must persist in the fundamental theory, line and strategy of the Party, to promote the integral five-part comprehensive arrangement, promote the strategic arrangement of the “Four Comprehensives” in a coordinated manner, and integrally deepen reform and openness; we must build on the new stage of development, implement the new development concept comprehensively, accurately and comprehensively, structure its new configuration, promote high-quality development and promote independence and excellence in science and technology, and ensure the people’s ownership of the country and continue to govern the country in accordance with the law, in the system of core socialist values, in guaranteeing and improving the living conditions of the people in concomitance with development and in the harmonious coexistence between man and nature, with a view to synergistically promoting the people to lead a comfortable life, to make the country prosperous and strong, and to build a beautiful China.”[23]

In the framework of this new era and after a century, it is important to persist in the teachings of Marxism, especially in the face of the new challenges ahead for China, as XI Jinping rightly states:

“In the new expedition, we must adhere to Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong’s thought, Deng Xiaoping’s theory, the important thinking of triple representativeness and the scientific conception of development; comprehensively implement the thinking on socialism with Chinese peculiarities of the new era; persistently integrate the fundamentals of Marxism with the concrete reality of China and with its excellent traditional culture; observe the era, understand it and lead it by using Marxism, and further develop the Marxism of present-day and 21st century China.”[24]

As we said at the beginning, the reference to the 3 principles stipulated by Hobsbawm could serve us to sift the Chinese communist party around a possible traditional theory of Marxism. Under this methodology the problem remains only under point one “the proletarian class political movement”, since the “triple representativity” thinking is obviously in conflict with the principle of the proletarian movement put forward by Hobsbawm.

Strictly speaking, the Chinese Communist Party has applied the tactic of historical materialism and, as Jinping himself points out, “Marxism is valid to the extent that socialism with Chinese peculiarities is real”. However, at this point we must admit that Chinese Marxism and Western Marxism have a problem of measurability[25] to use an epistemic term. In the case of the West the verification criterion of Marxism has been built around “dogmatism with the text”[26].

Chinese Marxism, on the other hand, has built its criterion of truth around political practice, as Deng Xiaoping once said:

“According to our own experience, when we talk about socialism, the first thing we must do is to develop the productive forces, that is the main thing. Only in this way can the superiority of socialism be shown. To know whether socialist economic policies are correct or not, we must see, in the last analysis, whether the productive forces have been developed and the incomes of the people increased. This is a criterion above all others. To talk in a vacuum about socialism does not work, for the people will not believe it.”[27]

Therefore, the criterion of truth as far as Marxism and much else in China is concerned, is the development of the productive forces and the increase of the people’s income, around this revolves the whole criterion of truth, it is in this sense that “seeking truth in facts” must be understood, for Western Marxists this could be defined as economicism, but for the Chinese in many respects it has meant survival.

Translation: ALAI

References

[1] Hereafter CPC.

[2] Excerpt from the speech delivered on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the reform and openness (1978-2018) at: http://spanish.xinhuanet.com/2018-12/18/c_137681901.htm

[3] “It is well known that, after Hua Guofeng, Mao Zedong’s designated successor, was removed from power, and especially following the implementation of capitalist policies by Deng Xiaoping, and the progressive building on these by his successors, the Chinese government and the Communist Party gradually abandoned the principles of Marxism and moved towards the opposite pole of the political spectrum, until finally coming to adopt principles such as those established by the ideologue of fascism, Vilfredo Pereto: iron control in politics and total laissez-faire in economics. Capriles, Elías “El capitalismo imperialista y casi-facista chino vs. El marxismo libertario del Dalai Lama” in Humana del Sur, Tíbet: Religión y política, Mérida, Venezuela, July-December, 2013, Year 8, number 15, p 16.

[4] Eric Hobsbawm. Cómo Cambiar el Mundo. Marx y el marxismo 1840-2011, Barcelona España: Editorial Crítica, 2011, p 59-109.

[5] Eric Hobsbawm Ob. cit. P.71

[6] Excerpt from Xi Jinping’s speech during the centenary of the CPC (1921-2021).

[7] This distancing could be situated in 1939, when Mao wrote the pamphlet The Chinese Revolution and The Communist Party… in it he concludes: “the driving forces of the Chinese revolution lie in the countryside… The youth and the historical strength of the Chinese peasantry” This position is in many respects somewhat distant from the traditional Leninist theory of the proletarian vanguard. Mao Tse-Tung. Obras Escogidas Tomo II, Pekín: Ediciones en Lenguas Extranjeras, 1972, p.335.

[8] Mao Tse-Tung (Vol. V) Ob. cit. P.563

[9] Young people, mostly from high school who identified themselves with Maoist doctrine and who acted even outside the party.

[10] Deng Xiaoping. Textos Escogidos Tomo (II) (1975-1982), Beijing: Edición en Lenguas Extranjeras, 2013, p.348.

[11] Deng Xiaoping- Ob cit,. p. 53

[12] Ibid.

[13] Deng Xiaoping. Ob. cit. P. 151

[14] The first to speak of the great project of the modestly affluent society was Deng Xiaoping in an interview with Japanese Prime Minister Masayoshi Ohira on 6 December 1979.

[15] Deng Xiaoping. Ob. cit. P.347-350.

[16] Excerpt from the speech delivered on the occasion of 40 years of reform and openness (1978-2018) at: http://spanish.xinhuanet.com/2018-12/18/c_137681901.htm

[17] Deng Xiaoping. Ob. cit. P. 267-268.

[18] Excerpt from Jiang Zemin’s report at the 16th Congress of the CPC at: http://spanish.china.org.cn/spanish/50593.htm

[19] Perhaps one of the most curious examples of this inclusive possibility of entrepreneurs in the party is Jack Ma, CEO of Alibaba Group and China’s richest man.

[20] Excerpt from Xi Jinping’s speech for 40 years of reform and openness (1978-2018) at: http://spanish.xinhuanet.com/2018-12/18/c_137681901.htm

[21] JINPING XI, 2014, La Gobernación y Administración de China Tomo II, Beijing, China, Edición en Lengua Extranjera, 8 pág.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Excerpt from Xi Jinping’s speech at the 100th anniversary of the CPC (1921-2021).

[24] Ibid.

[25] Here we use Paul Feyerabend’s epistemic proposal on the thesis of incommensurability and the problem of comparison without shared criteria of measurability.

[26] Eric Hobsbawm. Ob. Cit. p.26-57

[27] Deng Xiaoping. Ob. cit. P.350