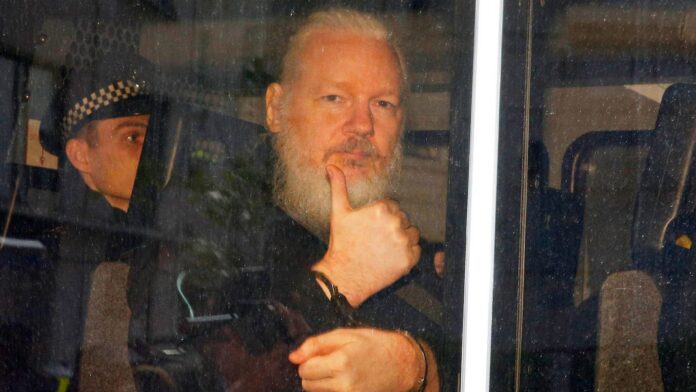

This Monday, April 11, Julian Assange completed three years in the Belmarsh maximum security prison in London, where he awaits a decision on the US extradition request. Together with his previous confinement in the Ecuadorian Embassy, this adds up to more than 10 years of ferocious political and legal persecution against the Wikileaks co-founder and journalist, without his being convicted of any crime. The US is charging him with 17 counts relating to obtaining and publishing classified documents under the country’s Espionage Act, and which could lead to a 175-year prison sentence.

In mid-March, the UK Supreme Court refused to hear Assange’s appeal against the extradition order emitted last December 10 (Human Rights Day!). The Court stated that his appeal, based on the grounds that his health would be further affected by US incarceration conditions, had “no arguable legal grounds.”

From there the decision to extradite or not passes to Home Secretary, Priti Patel, and the defense has four weeks to make representations which she must hear. If Patel does authorize extradition (which seems likely), the matter returns to Judge Baraitser at the original magistrate’s court, for execution.

However, this could open new opportunities for appeal, since the appeal process that has recently concluded was initiated by the United States government, against Baraitser’s original ruling denying extradition (subsequently overturned by the High Court) on the grounds of possible threats to his health.

But Assange himself has not yet appealed to the High Court, and he can do so, once the matter has been sent back to Baraitser by Patel. According to journalist Craig Murray, several of the grounds on which Baraitser initially ruled in favour of the United States could be motives for appeal, in particular:

- “the misuse of the extradition treaty which specifically prohibits political extradition;

- the breach of the UNCHR Article 10 right of freedom of speech;

- the misuse of the US Espionage Act;

- the use of tainted, paid evidence from a convicted fraudster who has since publicly admitted his evidence was false;

- the lack of foundation to the hacking charge.”

In the convoluted appeals process, these points have not yet been considered by the High Court. As Murray observes: “it means that finally, in a senior court, the arguments that will really matter will be heard… now the High Court will have to consider whether it really wishes to extradite a journalist for publishing evidence of systematic war crimes by the state requesting his extradition.” This would mean, at least, that the extradition could not be executed immediately, but for Assange it is likely to result in at least another year in the Belmarsh prison.

Transparency and surveillance: democracy upside-down

This brings us to the crux of the persecution against Julian Assange. In democratic societies, governments have the obligation to protect human rights – among them the privacy and security of their citizens. They are also expected to practice transparency and accountability with regard to public policy, since their mandate emanates from the people, the electorate, and their budgets are largely funded with their taxes. Yet it seems that today’s surveillance society turns these principles upside-down, when governments and corporations act in collusion to flagrantly violate people’s privacy and security, while they seek to conceal many of their own actions under a blanket of secrecy.

Clearly, the massive violations of privacy and the loopholes in digital security that are coming to light in recent years are not due to accidents or malfunctioning of the system. On the contrary, they are an integral and essential part of the present financial model of internet development. A model based on massive collection and monetization of data – with or without consent of those who provide the data –, via the development of mega platforms that offer “free” services; and this with a minimum – or absence – of regulation. Meanwhile, governments, security agencies, political groups and others frequently enter into agreements with the corporations that manage these platforms, to gather data for surveillance purposes, including political manipulation (such as the infamous Cambridge Analytica case) and containment of social protest and political dissent.

It is in this context that Wikileaks and Julian Assange have rendered an important service to humanity by demonstrating that this digitalized society can also work in favor of more democratic governance. They have enabled people to monitor the actions of those who exercise power and have exposed abuses of that power, among other things by providing opportunities for whistle-blowers to reveal irregularities committed by public or private institutions. While the surveillance society spies on people for those in power, Wikileaks takes on the task of liberating information so that it is available to the people.

As Noam Chomsky has exposed, since the early years of the past century, the democratic freedoms won in countries such as the USA and the UK meant that those in power could no longer maintain social control mainly by force. They had to change their power strategy to implement control by manipulating opinion via the media and public relations, what he calls “manufacturing consent”. But that also implies that those matters that are incapable of generating consent must be kept in the dark. Thus—he underlines—, the unpardonable “crime” of Assange and Wikileaks is that they have lifted the veil of secrecy that protects the powerful from scrutiny; and by doing so, they could cause power to evaporate. Chomsky adds that the archives of declassified documents reveal that official secrecy has little to do with state security (cited as the pretext) and a lot to do with hiding from the public decisions that could affect their interests or their livelihoods, or undermine their support for their governments.

Among the examples of such “inconvenient” revelations was the publication by Wikileaks of several chapters of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement, when it was being negotiated in secret primarily for the benefit of the large corporations; revelations that enabled people’s opposition movements to respond in a timely manner. Also, the Iraq and Afghanistan war logs, released by military whistle-blower Chelsea Manning, which detail the indiscriminate killing of civilians during the US invasion and occupation of those countries. However, no doubt what most aroused the fury of the US government was the publication, as of March 2017, of the Vault-7 CIA files, that detail activities and capabilities of the Central Intelligence Agency to perform electronic surveillance and cyber warfare.

Wikileaks and Julian Assange have received numerous awards and tributes for these contributions to public knowledge, in recognition of their journalistic input, their defense of human rights and freedom of expression and their political courage.

At the same time, they have been submitted to a constant bombast of defamation attempts, since the most effective means those in power use to undermine public support for those they consider adversaries is to thrown doubt on their credibility. And this is not just speculation, as Australian journalist, John Pilger, has revealed:

“In 2008, a plan to destroy both WikiLeaks and Assange was laid out in a top secret document dated 8 March, 2008. The authors were the Cyber Counter-intelligence Assessments Branch of the US Defence Department. They described in detail how important it was to destroy the ‘feeling of trust’ that is WikiLeaks’ ‘centre of gravity’.

“This would be achieved, they wrote, with threats of ‘exposure [and] criminal prosecution’ and an unrelenting assault on reputation. The aim was to silence and criminalise WikiLeaks and its editor and publisher. It was as if they planned a war on a single human being and on the very principle of freedom of speech.

“Their main weapon would be personal smear. Their shock troops would be enlisted in the media — those who are meant to keep the record straight and tell us the truth.”

The strategy was largely successful, though even Pilger was astonished at certain journalists who gleefully took on this task of defaming a colleague without anyone telling them to do so.

On April 11th, the International People’s Assembly (IPA), along with other organizations, are promoting mobilizations on the streets, on social networks and through debates, for freedom and against the extradition of Assange. And in effect, it appears that, if Assange’s project is to liberate information for the people, his own liberation will depend primarily on pressure from the people on those in power.